This is my favorite interview printed in Deadly Pleasures Mystery Magazine in the 27 years of its existence. I learned so much from it and the stories told are fascinating. For someone who doesn’t like name-dropping, Stephen Marlowe does a lot of that: P. G. Wodehouse, Donald Westlake, Ed McBain, John D. MacDonald, Ellery Queen, Anthony Boucher, Richard Prather, Peter Rabe and Marvin Albert. Even if those people don’t get you to read this, read it anyway. It is a vivid overview of a writer’s life well lived. Ted Fitzgerald did a masterful job as the interviewer.

Interview of Stephen Marlowe (1928-2008)

By Ted Fitzgerald

The following is an interview of Stephen Marlowe conducted at the Monterey, California, Bouchercon in October of 1997.

Introduction by Ted Fitzgerald

Stephen Marlowe has lived the life most writers dream of. He has been a free-lance writer his entire career. He has been able to live in the south of France, among other places. And in all that time write an impressive body of work.

Stephen is a graduate of William & Mary. He began writing in his teens in the science fiction field. He came to New York City after graduation and went to work for the Scott Meredith Agency. He began writing on his own and became one of the premier writers of suspense fiction in the 1950s, especially in the area of paperback originals. His trademark series during this time was the Chester (Chet) Drum series, twenty books written for Fawcett Gold Medal between 1955 and 1968. In the mid-1960s he moved to Europe and in the late 1960s began writing large-scale suspense and thriller novels. Since the 1980s he has been writing something quite different – literary historical novels, the latest of which is THE LIGHTHOUSE AT THE END OF THE WORLD. It has as its protagonist Edgar Allan Poe and features as a character Poe’s creation C. Auguste Dupin (arguably the first private detective created by an American). Stephen feels that with this book he has returned to the mystery field from which he started.

Ted: It has been said that you can teach people writing but that you have to be born a writer. You have been writing virtually since childhood. What brought you to writing? Were there any early influences?

Stephen: It was always with me. When I was about eight years old I published a neighborhood newspaper called the Daily Planet (probably taking this title from Superman). The only problem was that it came out once a week. At that age I didn’t realize that the Daily Planet wasn’t supposed to come out once a week. It was done on an old hectograph, if you remember that old copying device. It was a jellied thing and the print came out purple. It was generally difficult to read.

I started reading when I was very young and I enjoyed reading. And at some point I began thinking, “I can do this.” It is sort of like if a freelance writer works at home, as I do, after a while I wander into the kitchen and I see my wife cooking and I think, “I can do this.” And now I do a lot of the cooking in our house. And of course it is a question of thinking not only I can do this, but I want to do this. Any good writer that you read challenges you and what you write may be determined by what you read when you were very young.

As to early influences, Edgar Rice Burroughs comes quickly to mind. I read and reread everything he wrote again and again and again before I was ten. And somehow I think that some of what I read then is in my work.

Ted: Your first work was in the field of science fiction, in the fanzines. Were you writing during college?

Stephen: No, I started just after graduation. Not too long ago I was talking to my Dutch publisher and the subject of the year 2000 came up. He asked me how long ago did I publish my first short story and I told him that it came out in 1950. Then he said that we have to have a party in the year 2000 on the fiftieth anniversary of the publication of that short story. The party is to be in Paris with an attendance of exactly 50 people.

Ted: Like every writer dreams, you went to New York City to become a professional writer. One of your first jobs there was with the Scott Meredith Agency. That sounds like an interesting place to have worked at that time.

Stephen: Yes, it was. Don Westlake also worked there around that time and there were many other writers who cut their teeth there. Scott’s agency was fairly new when I joined it. It was only four or five years old and he paid terribly, but the experience was tremendous. Scott would never promote someone from within the company. He had about six or seven editors reading fee material from would-be writers (which I didn’t approve of anyway). He always wanted someone from outside to become his chief editor. I don’t know why. I had just gotten a job with a pulp magazine chain called, I believe, Popular Publications. I had only been there a week when one day Damon Knight, the science fiction writer, walked in and said: “Scott Meredith is about to advertise in the New York Times for a chief editor. Scott hates the idea of interviewing two hundred people, which is the expected response from his ad. If you run over there and he likes you well enough, he’ll cancel the ad and you’ll get the job.” And that is exactly what happened. With a great sigh of relief Scott hired me. I don’t think he cared who I was or what I could do. I stayed in his employ five months on two different occasions. I sold a couple of short stories and prematurely went free-lance, then I came back. After the second stint, I hired Evan Hunter (Ed McBain) to replace me. These were the type of people who Scott was hiring and all of us would get tremendous experience. Scott knew he wouldn’t keep us.

Ted: In this job you got a chance to meet some interesting characters including the famous British writer P.G. Wodehouse.

Stephen: Early on in my job as chief editor at the agency, Meredith had a call from Collier’s magazine, which many of you will recall was like the Saturday Evening Post. They had been alternating between a mystery and a western serial for some issues and wanted to try sandwiching in between those two genre serials a humorous one. Scott was asked if he had anyone working on such a thing.

This wasn’t too long after World War II and P.G. Wodehouse got into some trouble, rather naively, during the war. He was working on the Channel Islands where he lived and the Germans occupied the Islands. Because he was a celebrity they treated him well. After the war he was asked, “How did the Germans treat you?” And he said, “Well.” And so the word was that he was a Nazi. Which he wasn’t. He was just naive. Anyways, he hadn’t been published for some years. He hadn’t gone broke yet, but was living in a penthouse on Park Avenue in New York City, just waiting for someone to say, “We forgive you,” or, “We were mistaken.”

So Scott called Wodehouse, whom he had been an admirer of, and asked if he was working on anything at the moment. Wodehouse said that he wasn’t. Scott asked if he could pretend that he was, and Wodehouse said, “I don’t know.” Scott then suggested that he come to the office and that someone would take him around to the fiction editor of Collier’s magazine, whose name was Knox Burger. Knox Burger became the editor at Gold Medal Books some years later.

I went over and picked up Wodehouse, who was in his seventies by then and I was 22 and I shepherded him to the Collier’s offices. There was an elevator strike at that time in New York and he had had to walk down the stairs from the fifteenth floor. On the way I asked him if he had come up with an idea for the story that Collier’s wanted and he admitted that he didn’t. When we got to Knox Burger’s office, Knox asked him if he had an outline for the project and Wodehouse said nothing because he didn’t know what to say. I jumped in and said that he did, but that he had left it in his penthouse and with the elevator strike it would be difficult to get. Then Burger asked Wodehouse to tell him about it and again there was a long silence. I suggested that Knox give Wodehouse an office with a typewriter and let him rewrite the outline from memory. Wodehouse looked at me with a really rather severe look. I have a feeling Burger knew then that I was having him on, but he couldn’t say so. Wodehouse, with a small gulp, said, “Sure.” He went into an adjoining office, while Burger and I sat opposite each other smoking and staring. And there was no sound from the office next door for about three to four minutes. Suddenly there was the tentative click of typewriter keys. Then it got a little faster and a little faster until suddenly it “went.” About 45 minutes later Wodehouse came out with an outline. Burger bought it and it was the first thing published by Wodehouse since the end of World War II. We’ll get back to Burger later, but I think that first meeting with him was unfortunate because I think he knew that I had put something over on him. And he had a long memory.

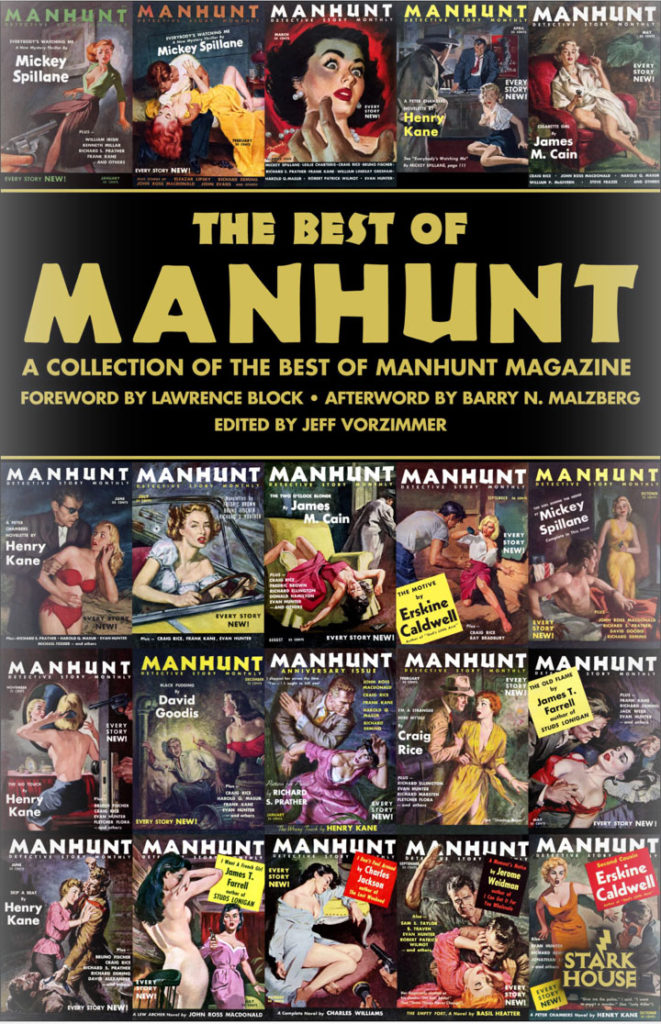

Ted: Around this time you began to write professionally and publish in both magazines such as Manhunt and Accused and others of the time – and also began doing books. Did one come before the other?

Stephen: First came the science fiction. There was a man named Howard Browne, who also wrote pretty good mysteries under the pen name John Evans about Paul Pine, a private eye. Howard was the editor of Ziff-Davis Publications and I got to know him. He would call me and say, “I have a cover illustration. Would you write a story to go along with it?” With my early science fiction I did quite a lot of that.

But then I think that we have to jump. I wrote science fiction prolifically for a couple of years and then I got drafted into the Army during the Korean War. In the last year of military service I had a very difficult assignment, that of being stationed on Governor’s Island in New York. I was in charge of the sports page of the Army newspaper that came out every two weeks. My superiors thought this was a full-time job. I was a corporal and they gave me a driver and a secretary and unlimited access to any sports event in the whole First Army area, which included New England, New York and Pennsylvania. I would watch things like baseball games with Whitey Ford on one team and Harvey Haddix on another. One page every two weeks gave me a lot of free time to work on other things. Someone here at the convention has a copy of an Ace Double which contains my story entitled CATCH THE BRASS RING. That is a story I wrote while on this arduous Army duty. I did one or two other novels during that same period. When I came out I did a little more science fiction for a year or two, but gradually switched over to writing paperback originals. Chet Drum, my private eye, probably got going in 1955.

Ted: The Drum series was a unique series for the time. For those who are not familiar, Chester Drum figured in twenty novels and several short stories. He was a private eye with a difference: he was based in Washington, D.C., which then and now is still a rare location for a private eye to work. Instead of prowling the mean streets of the District, Chet would go to exotic foreign locales. He was probably the first international detective and one of the first whose private life outside of the case was fully chronicled.

How did Chet Drum come to be? The first book in the series could be a stand-alone novel. Did you have in mind a series from the beginning?

Stephen: I wish I could remember. I would guess that subsequent Chet Drum novels grew out of the response to the first. I was writing a private eye novel because I had never written one before. What I like to do whenever possible, even now, is challenge myself with something new – something which I find difficult because I haven’t done it before, and work on it absolutely as hard as I can. Working hard is more fun to me than not working hard.

Let me tell you how Drum got his name. When I was in the Army I was stationed at Camp Drum, New York, with the 87th Airborne Division in some kind of winter training exercise. And Camp Drum is Chet Drum. The exercise had a somewhat amusing ending. The notion behind it was that the exercise was to be the biggest mass airdrop ever attempted. But the weather was so cold and the ground so frozen, the powers that be opted to tailgate it. We just jumped out of the backs of trucks to simulate an airdrop. I hope that Chet Drum has fared better.

Ted: Let’s talk about the travel in the Drum series. There is one book where you keep him in North America, but all the others find him going to other continents. The books are written with great authority in terms of the setting. How many of these locations had you visited prior to writing each Drum novel?

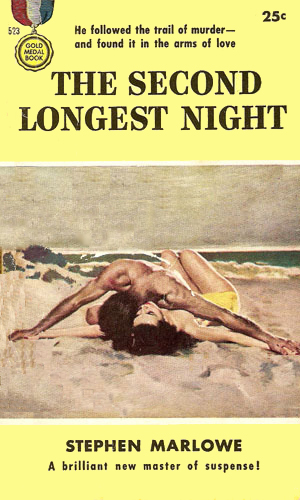

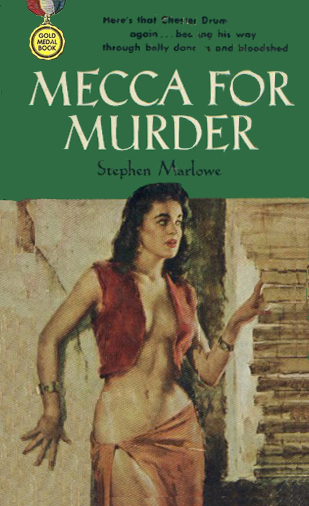

Stephen: The first couple of books were THE SECOND LONGEST NIGHT and MECCA FOR MURDER. The latter everyone tells me is very hard to find (I have a copy of almost none of the Drum books). In THE SECOND LONGEST NIGHT the background was set partially in Latin America, which, at that time, I hadn’t been to. In MECCA FOR MURDER it is obvious that I hadn’t gone on the pilgrimage to Mecca. But from then on I tried to visit the locale because I said to myself, “Hey, wait a minute. Drum is having all the fun.” It wasn’t that I went to a specific place so that I could write a book, it was because I had been to a specific place I then could write the book – or something about a place grabbed me. It started me on a lifestyle-changing travel kick.

Since Ann and I got married in the middle 1960s, we have spent about 25 years abroad. In the last 12-14 years we rarely returned to the U.S. – only for the birth of two grandchildren to check if the babies were real and had the requisite number of fingers and toes. At the end of that 14-year period we found ourselves in Paris and remarked that we should go somewhere really exotic and truly foreign. I said, “I know, let’s go to the U.S.” A little over two years ago we came back and temporarily settled in Connecticut.

My traveling lifestyle may be considered strange and most writers may not understand it. Anyone who writes wants what the Spanish would call, in bullfighting terms, a querencia, a safe place. It is a place that the bull can go and the matador cannot follow or he would get in trouble. Most writers need a place like this, a study where they will not be disturbed. Everything in the study has to be just right. When I begin writing a book I want to move about every three months. I want to go someplace else and get a whole new input that has nothing to do with the book. It is my safe place. This is the way I have been writing for the last 25 years and it works for me. I don’t know why, but I am not fighting it.

Ted: While you were doing the Drum series, you had characters come in and out of Chet’s life. One was Marianne, who appears in the first novel of the series and is still around for the last, with the implication that she is not a casual interest of his. This was a woman who had a professional career as a single mother, highly unusual for the time. Was Marianne modeled after anyone?

Stephen: I think that she just came out of my head. When I began writing about her, she wasn’t going to be a career-woman single mother. That developed over the course of the books. And in the last book Drum either proposes or nearly proposes to her and she didn’t want it because of his dangerous lifestyle. Remember that her late husband had been killed violently. At that point Drum is left up in the air and it is apparent that I had no intention of stopping the series then, but for a variety of reasons I did.

Ted: Chester Drum was a very popular series with Fawcett Gold Medal. Along with Richard Prather and John D. MacDonald you were a mainstay at Gold Medal. So what caused the end of the series?

Stephen: The decision was sort of made for me. I mentioned Knox Burger earlier in relation to the P.C. Wodehouse episode. I don’t think that he liked me. One time, for example, at the Overseas Press Club, I was talking with Hal Masur, the mystery writer. He was also a very gifted investment specialist. I had a little money and I was asking Hal about investments. Knox Burger walked over and asked with a frown on his brow, “What is this nonsense of a couple of writers talking about investments? You guys are supposed to be living in garrets and suffering for your art.” There came a time when Knox said to Scott Meredith, “I don’t care what Tony Boucher and others say about Stephen Marlowe’s Chet Drum series. I don’t like the series.” He said the same thing about other writers too; one was Marvin Albert, who was a really good friend of mine. Much later, after Knox was long gone from Gold Medal, Marvin went back to Gold Medal and wrote two good series for them, which had nothing to do with Knox Burger. Another writer whose work he didn’t like and who was almost destroyed by Knox was Peter Rabe. Peter was a pretty good writer and a very serious man. Knox was always trying to tell him what to write, which I don’t think is an editor’s job. I think you write what you have to or what you want to and they publish it or not. Well, the rapport was wrong between us and while the rapport was wrong my first hardcover suspense novel, THE SEARCH FOR BRUNO HEIDLER, was published. And also around that time, Anthony Boucher, the renowned New York Times critic, who indeed liked my stuff, wrote in his year-end summary of the mystery field, “Stephen Marlowe is the most prolific mystery writer in the United States.” I was shocked and dismayed. I didn’t want to be the most prolific anything. I wished he said I was the best or trying to be the best. At that point I took my then family off to Spain and I wrote a long historical novel, which was the first one of those that I published. I wanted to stop this reputation of being “the most prolific mystery writer” from taking root. Then I did a couple of hardcover suspense novels, one of which became a film which starred David Janssen (The Fugitive). But given the kind of life that Ann and I were then living (in little villages in the south of Spain or in Yugoslavia), we never got to see it. I have heard from people that it is quite good.

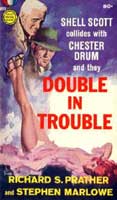

Ted: You collaborated with some popular authors of the ‘50s and ‘60s. Let’s start with Richard Prather. His character, Shell Scott, was a very happy-go-lucky, light-hearted character. Chet Drum, on the other hand, while not dour, was far more serious. The humor in the Drum books is more wry and subtle. How did you and Richard decide to combine these two seemingly disparate characters into a novel?

Stephen: There was a man named Dick Carroll, who was a “black Irishman.” He was very dour, except when he smiled and then he would light up a room. He was the man who really began the Gold Medal series of paperbound originals. It was his notion to publish paperback books as good in quality and originality as those being published in hardback. At one point Dick Carroll said to me, “You know, you and Richard have these two big-selling detectives. And you both have the same agent. Why don’t you put both of them in one book?” I wrote a letter to Prather mentioning this and Carroll wrote another letter showing support for the idea and both letters were sent out together. The idea immediately appealed to Dick as well. We plotted it on the telephone over a period of a few weeks. We decided to write alternating chapters. Each protagonist would begin to suspect and then be certain that the other protagonist was not on the side of the good guys. They went on this way for most of the book, until they meet near the end in what Ann insists is a humorous scene (I hope she’s right) and have an epic fistfight. The fight was narrated in shorter and shorter takes. Dick would do a slab of narration in which Shell Scott was being beat on rather hard, but he was narrating as if he wasn’t. Then I would do the exact same thing for Drum. The alternating narrative became shorter and shorter until both were nearly wiped out. Then the real villains enter the scene and Scott and Drum pick themselves off the floor and work together and win. In some ways the collaboration worked. When we were writing the book, because it got plotted by telephone, it got really too big. The original manuscript was 800 or 900 pages. For a private eye novel, it was just too big. So it was decided that I would fly out to Richard’s home in Laguna Beach, California, and that we would cut each other’s parts, with his wife, Tina, acting as referee. And Tina was really good in that role. She would say, “Hey, Dick, you don’t really need this line, do you?” He’d scowl at her. “C’mon, Dick, you really don’t.” Then Dick would say, “Well, Steve, how about this undeathless line of prose here?” And we spent about three weeks cutting each other’s prose to ribbons, but it worked. And after a while we came to admire and respect what we were doing to each other. But without Tina I don’t think it would have been possible. She was really great. And we remained very cordial afterwards.

Ted: It sounds like one of those rare collaborations where you end up speaking to each other. You wrote under a number of pseudonyms – C.H. Thames, Andrew Frazer, Jason Ridgway and Adam Chase. There was one pen name of yours that I ran across which really intrigued me and that is Ellery Queen. How did you come to write under that name?

Stephen: After my very first trip to Europe as a tourist I wrote a novel based on the itinerary that I took. I gave it to Scott Meredith to sell and a year passed and no one seemed to want it. One day Scott called me and said, “Remember that book you wrote called DEAD MAN’S TALE?” Well. I’ve sold it.” I said, “Great. Who is publishing it?” I asked. He stammered for a second and then told me that it was going to appear under someone else’s name. “Why?” I naturally asked. He said, “Well, look, I couldn’t sell it in any other way.” “Whose name will it appear under?” “Ellery Queen.” I said, “Well, Scott, I don’t want to do that.” There was a long silence followed by “Steve, I’ve got a problem because I signed a contract saying you would do it.” Which he shouldn’t have done. After another long silence, I said, “OK, Scott, just this one time.” “But Steve, I signed a four-book contract for you to do it.” I then replied quite firmly, “Scott, I’m not going to do it.” He said, “Gee, you’ve really got me in a bind. What if I got three writers to ghost the books for you?” I was young and hungry. I probably should have said no, but I didn’t. He got three pretty good professional writers, whom I won’t name, to do the job. The first book was published (the one that I had written). Then the second one came in and I had a chance to vet it and found it pretty good. It was passed on to Fred Dannay, who called Scott and said, “I think Steve Marlowe is slipping.” I think the others were published but I heard that Fred was never as happy with them as he had been with my first book.

Ted: Did you get paid for the three books you didn’t write?

Stephen: I think I got some part of the money, but it wasn’t much. That wasn’t my idea, it was Scott’s idea. Scott was a very successful agent but he could have been selling shoes, real estate plots or houses. With him it was the unit that he was selling. This is not entirely what an agent ought to be. An agent ought to care about books. Scott claimed he did, but he didn’t. When that became more and more evident I finally left him.

Ted: Tell us about the collaboration with John D. MacDonald.

Stephen: Every year Mystery Writers of America produced from its membership an anthology of short stories, each with a different nature. I forget whose idea it was, perhaps it was mine, to have an anthology in which each of a bunch of very good writers would write a chapter. The premise was that there was a bomb on an airplane and the question was: which passenger was the bomb set for. Each writer would write his chapter on a specific passenger, giving reasons why that passenger was the intended victim. John and I got together and assigned the various chapters to the writers– such professionals as Bart Spicer and Hillary Waugh– giving them a rough idea of what we wanted. Periodically John and I would get together to read the very well written chapters. Clayton Rawson, the then editor at Simon & Schuster, who was going to publish the book, met with us over lunch at the Oak Room at the Plaza in New York. Clayton said, “You know, this stuff really looks terrific. Now one of you is going to have to wrap it up with another character who solves the whole thing.” John and I looked at each other and we each suggested the other for the task. John and I talked for hours as to how to finish the project, but we were stymied by the fact that each writer had done his job too well. Each passenger was the absolute number one suspect for being the bomb target. We could never decide who was the real intended victim, to such an extent that we went back to Clayton and said, “Hey, Clayton, we can’t do it.” Clayton accepted the impossibility of the project and said that the chapters would have to be published individually by the separate authors. So the anthology was abandoned. Perhaps John and I were being lazy, but I don’t think so. The writers just did their work too well.

Ted: When you wrote the last book in the Chet Drum series, did you know it was the last book?

Stephen: No, I don’t think so. There were two things going on in that book that were unresolved. One was Chet’s relationship with Marianne Wilder. He still wanted this woman on a permanent basis. And then there was the notion of the Spanish gold. It was either the second or third book which featured in some way a character that I rather liked named Axel Spade. Let me parenthetically go back. One year I was living in Greenwich Village and I read an article in the Saturday Evening Post about a man named Franz Pic. Franz Pic was a man who was known as the black marketeer’s best friend. He had a black market annual, which, for example, told people how to change utterly obscure currencies into good money, thereby circumventing the laws of various countries. Franz Pic was wanted by the law in about 25 countries, but not in the U.S. and in France, which were his two main bases of operation. I patterned my character Axel Spade after Franz Pic, pique being “spade” in French. The first book of the Drum series in which Axel Spade appeared came out and the first day that I saw the book on the newsstands my phone rang. The man on the other end of the line said, “Hello, my name is Franz Pic and I see that you have put me in your book.” I said, “Yeh, I guess I did.” And with that he invited me to lunch. At lunch he gave me this huge black market compendium, which I would use subsequently. We had lunch several times and he was always telling stories that were fascinating. He obviously had nothing to do with the vast Spanish gold supply (the subject of the last few Drum books). When the Spanish Civil War began, the Spaniards sent most of their gold reserve to Moscow for safekeeping. It disappeared. And it was a fairly large gold reserve. Axel Spade said in the first Drum book that he appeared in that he had a way of getting the gold back. And they worked on this through the last published book in the series and left it unresolved. I thought that I had a way to resolve the gold reserve plot line and I would have liked to do it, but for reasons that I mentioned earlier, the series just stopped. So perhaps somewhere in Geneva Chet Drum is sitting in his European office waiting for Axel Spade to arrive with his plan to get the gold.

Ted: So there weren’t any unwritten or unpublished Drums, because you were doing other work.

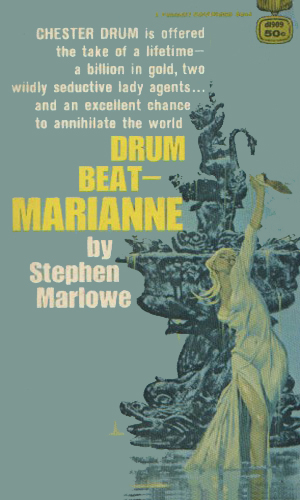

Stephen: I wrote DRUM BEAT– MARIANNE while Ann and I were living in a small village in Yugoslavia as part of a long honeymoon, which may still be going on for all I know. We took the manuscript to a Yugoslav post office, paid a large sum of dinar and were assured it was on its way to my publisher in New York. About six or seven weeks passed. I got a letter from Scott Meredith saying the manuscript never arrived. After ten weeks another letter said that the manuscript still hadn’t arrived. We believed it to be lost in the mails, so Ann retyped the whole thing from the carbon copy and we mailed it again. And just the day that we mailed it, we received another letter from Scott telling us that the original manuscript had finally arrived. It was sort of the last straw. At that time I was writing alternating Drum and hardcover books anyway, so I just concentrated on the hardcover from then on. One of the hardcovers, a novel called THE SUMMIT, is exactly what it sounds like. A sort of double-meaning title of a story which took place in the Swiss Alps. And it was about a summit meeting between an American president and a Russian leader. The Russian leader disappears on the eve of the summit. And it was a pretty successful book. I was lucky enough to have Anthony Boucher say it was the best intrigue novel of the year, and it sold in quite a few countries. Its success impelled me to write more of the same. So the next book I wrote — a long historical novel about the painter Goya!

Ted: Did you know Anthony Boucher well?

Stephen: I would meet Tony every now and then in New York because I was often at the MWA dinners. There was a period of about three years when I was living in New York and served as regional vice president of MWA. And whenever Tony would come in we would have drinks and talk. He was a really nice guy. He knew the field and loved the field. I couldn’t say that we were friends, but we knew each other fairly well.

Ted: Let’s jump forward a little. You did these hardcover novels for several years. Then there was a gap of time when we didn’t hear Stephen Marlowe’s name for a while. Then we began to see your name on a book about Christopher Columbus, a book about Miguel Cervantes and a book about Edgar Allan Poe. In many respects this is quite different writing. In general how did this come about? What changed?

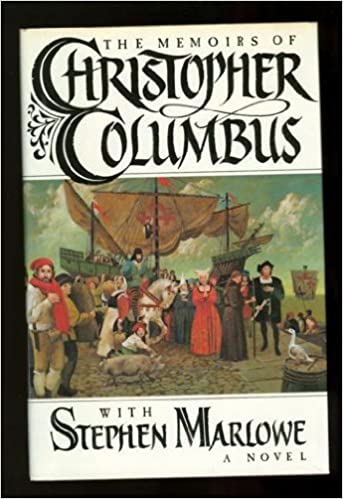

Stephen: We were in Europe then pretty steadily. I arrived at a point when I didn’t know what I wanted to write. I thought for a while that I had written myself out. Because at the time I had already had a pretty long career. This was about 12 years ago. For almost three years we wandered around Europe going picturesquely broke in places like Gstaad, Paris and the south of Spain. I was writing nothing to speak of – little starts of books, mostly just notes to myself. And three years passed. One morning, while living in a house on a cliff overlooking the Mediterranean, in the south of Spain, I went to my typewriter, looked out the window and typed the first scene of a book that I had no notion that I was going to write the day before. It was the best act of pure inspiration I ever had. I’ll never have one like it again, I’m sure. I gave it to Ann to see what she thought of it. She said, “Oh, wow! What happens next?” I told her that I didn’t have the slightest idea, but that I was going to find out. Then I did some research. Let me pause for a word of advice. If you are writing something historical, to do the research first is probably a mistake, because then it sticks out. I think the best way to do research is to just keep up the research with the writing. The end product of that morning’s work was THE MEMOIRS OF CHRISTOPHER COLUMBUS.

Let me tell you of the checkered history of this book. At the time I finished with the book Don Congdon was my agent. After sending it to him for comment, I didn’t hear from him, so some time later I cabled him asking what he thought of it again. He cabled back saying “My letter in the mail contains certain reservations about COLUMBUS, but LittleBrown very enthusiastic first reading.” So we went out and celebrated because it sounded very good. Then his letter came. He didn’t understand the book. The book is a false memoir, anti-historical and funny – at least some people have said it is. And he didn’t get any of that. He wondered why people would give Columbus so many great “credits” if he was such an anti-hero as I depicted him in my book. I sent him back a cable saying, “If LittleBrown doesn’t buy you’re fired.” He was nice enough to send me the letter in which they didn’t buy. It was a three-page letter from Bill Phillips, who I believe was their chief editor, saying that he loved the book tremendously, but he wasn’t sure of the market for it. I had the strong feeling that if my agent had sent it to him with some enthusiasm he might have bought it.

So I thought, “What do I do now?” I knew a few agents, so I sent it to one – Carl Brandt, who sent it back with the note “Not saleable.” I then sent it to Richard Curtis who replied with “We have remarked certain anachronisms, anticipations of future history and similar anomalies which spoil the authenticity of this work. We suggest you excise all such references.” I sent it to one more agent who also didn’t think it marketable. Still I had perfect faith in the book. I knew it was the best thing I had ever written and I was frustrated. Ann, who has written three books, had a leftover English subagent named John McLaughlin, so she suggested that we send it to him. Two weeks passed and John phoned us in the south of France saying that he considered it magnificent, saving my life. He put it on auction at Christmastime when all the publishers in England go home to read. He said that on January second they were all knocking on his door. Finally Jonathan Cape took it for what in England at the time was a very high advance. Cape then was probably the most prestigious publisher in England. And from that the whole world became interested in the book, including the U.S. Within a month there was an auction here. The French gave it an award as the best historical novel of the year. I explained to them that it was intended as an anti-historical novel and they said, “Never mind, we still want to give it this award.” In the States I had my son-in-law, who had been in publishing, take it around to some of the publishers, including Random House. And Bob Loomis loved it, but sent it back. Then he changed his mind and asked for it again — only to reject it again. And a third time he wanted it back. It was Random House that put in the floor on the auction. But then Scribner’s came through with a preemptive offer, which means that you have 24 hours to say yes or no and you cannot talk to any other publisher about the price of the offer. I asked if we could talk to just one Boston publisher – LittleBrown because they had come so close before. The response from LittleBrown was “I don’t know why we didn’t buy this book when it was presented to us last year.” However, they couldn’t match Scribner’s price so Scribner’s did it. The Scribner publisher is now my agent and she is tremendous.

Question from the audience: What is the story behind the three book-series of Believe It or Not books?

Stephen: A man whose name I forget owned the rights to Ripley’s Believe It or Not. He contacted me and asked, if he gave me access to all of the Believe It or Not files, would I write some mysteries about them. I did four books under the name of Jason Ridgway about the Believe it or Not files. Those books made me become an expatriate in a rather odd way. A television producer wanted to do a television series based on the Jason Ridgway mystery series and he insisted that he wanted me to be the producer, a job which I had no experience in. We met for lunch in the Oak Room in New York. The producer was very charming and enthusiastic but, fortunately for me, because I really didn’t want to do the project, he was a name-dropper. As someone famous would come by he would say something like, “There goes Marlene Dietrich. Hello, Miss Dietrich.” She would look at him blankly and nod as people will. And a few more people would pass to the same treatment and I was getting more and more jaundiced at the whole thing. Finally the actor Dan Duryea came by. He said, “There’s Dan Duryea. Hello –” And before he could finish the line I got up and went over to Duryea, pounded him on the back and said, “Hi, Dan. Long time no see.” He shook my hand and said, “Yeh.” I had never seen him before in my life. And I just kept walking and left the room. And then I went to Spain.

Ted: I am curious as to why you adopted your pseudonym as your legal name – something that Evan Hunter also did.

Stephen: When Evan did it he had written a paperbound original, probably for Popular Library, under the pen name Evan Hunter. All his family got together and told him that he had to write under his own name. But his publisher really preferred the name Evan Hunter. He thought long and hard and told his family, “Look, I’m in the business of writing books. If the publisher says use this pen name, I’m going to use it.” After a little while he thought that if he had the name he might as well have the game, so he legally changed his name.

In my case I was writing suspense novels under the name Stephen Marlowe for a couple of years. I was on a trip to Scandinavia and there was a party for me in Stockholm, organized by some Swedish mystery writers. They came to my hotel to get me, but obviously I had registered under the name on my passport. They couldn’t find me. I got to the party late and it was embarrassing. I explained to them what the problem was, but that was the straw that broke the camel’s back and as soon as I got back to the States I changed my name legally to Stephen Marlowe. And the rest is history – or anti-history.

Ted: What are you working on now?

Stephen: I am tinkering with the notion of combining my love for history (or anti-history) and my love for suspense in one book. And I think I can do it. I think I am going to try and do it, but that is all I am going to say about it now.

[Comment by George Easter, Editor. When I saw that Stephen Marlowe was going to attend the Monterey Bouchercon, I scrounged up a lot of his paperback originals, including ones he wrote under pen names, and took them with me to the convention and got them signed there. When I met Stephen and his wife, I found them very congenial. He talked a mile a minute and it was all very interesting and memorable. I treasure those signed books now — as I do the memories that this interview brings to mind.]